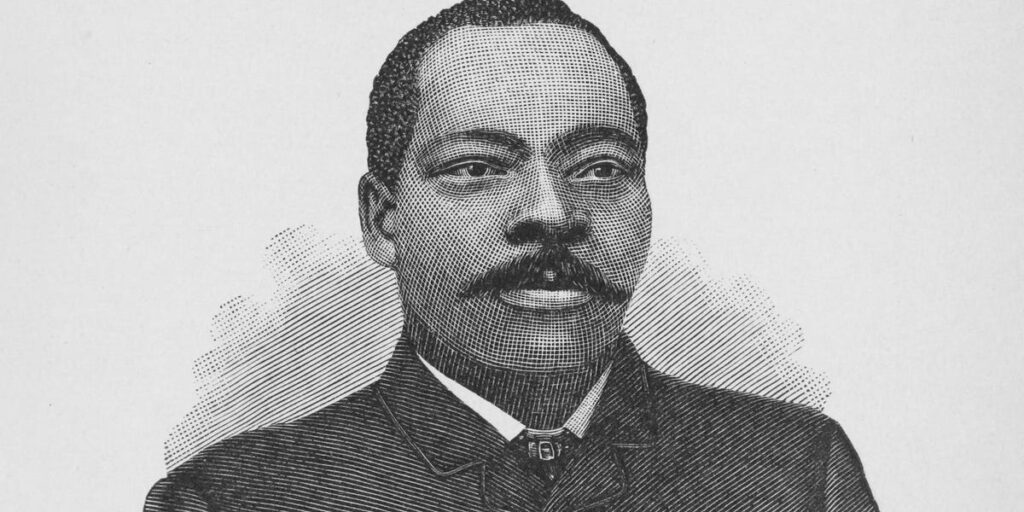

- Granville T. Woods was one of the most prolific Black inventors of the 19th century.

- In the 1880s, Thomas Edison sued Woods twice, claiming that he had first invented the telegraph for trains.

- Woods’ inventions revolutionized transportation, but he faced many challenges as a Black inventor.

Thomas Edison is widely considered one of the most famous inventors in American history, pioneering technologies such as the incandescent light bulb, the phonograph, and the motion picture camera.

Edison was a genius in his own right, but some historians say he also had a penchant for acquiring patents from other inventors.

One such inventor was Granville T. Woods, the most prolific Black inventor of the late 19th century. Woods is considered the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War, and was associated with other prominent inventors such as Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and Frank Sprague.

In 1887, Woods obtained a patent for the induction telegraph, which allowed messages to be sent between moving trains and railway stations. What he discovered was a much needed improvement in the communication system at the time, which was slow, inefficient, and could lead to train collisions.

Shortly after Woods implemented his invention, Edison sued Woods, arguing that he had created a similar telegraph first and thus had patent rights. Woods eventually won the patent battle, but the victory came at a great financial and personal cost, according to many historians.

“Woods’ life – sometimes closer to a nightmare than the American dream – vividly describes the harsh realities of being a Black inventor at the end of the 19th century,” said historian Rayvon Fouché wrote “Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation: Granville. T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer and Shelby J. Davison.”

Woods, ironically, was called “Black Edison” in the newspapers of the time because of his contributions to science.

Woods’ inventions revolutionized transportation

Woods was born in Columbus, Ohio, to free African Americans in 1856. When he was 10 years old, Woods had to drop out of school because his parents could not continue paying for their children’s education.

Instead, Woods became an apprentice in a railroad shop, which became the springboard for his career as an engineer.

Woods went on to have nearly 60 patents to his name. His innovations revolutionized the world of transportation, including the “Dead Man’s Handle,” an automatic brake that slowed trains when the operator was incapacitated. Woods also implemented an innovation that led to the “third rail,” an important way to provide electricity to trains to keep them moving, according to the United States Patent and Trademark Office and the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Many biographers say that Woods spoke and dressed in an elegant manner, often wearing all black. He sometimes referred to himself as an immigrant from Australia, which biographers believe was a way to gain more respect than if people knew he was African American.

The legal battle with Edison

Among Woods’ most important inventions was the synchronous multiplex railway telegraph, which allowed messages to be sent without interruption between trains.

Before he could file for a patent, however, Woods contracted smallpox and was bedridden for months. Historians describe how, upon recovery, Woods was shocked to learn that another inventor, Lucius Phelps, was credited for a version of the induction telegraph.

Woods diligently used notes, sketches, and a working model of his invention to prove that he had started developing the technology first, and won a patent in 1887.

But the patent war did not end there. Shortly thereafter, Edison sued Woods not once, but twice, claiming that he had first invented the inductor telegraph. Woods successfully defeated both cases, according to many historians. Other writers have suggested that Edison offered Woods a job at the Edison Company, which Woods turned down.

The challenges of being a Black inventor

Woods eventually sold some of his patents and devices to Edison and other industrialists, as well as companies such as Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Historians attribute Woods’ decision to sell his patents to a recognition that it was difficult to sell Black American inventions to a predominantly white audience.

“Like most other Black inventors of the time, Woods had to agree that the race of the inventor affected the market value of the invention,” writes Michael C. Christopher in the Journal of Black Studies.

Some of the people who bought Woods’ inventions didn’t pay him fairly, or failed to give him credit for his work, according to historians. Sometimes, inventors lose all rights to their inventions once sold, and receive no income.

Woods died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1910, impoverished and almost forgotten for decades. He was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006.