Black engineers have made many contributions to sound technology and music, overcoming systemic discrimination. And yet, they are often unknown, even today. One that anyone should know about sound is James West, who, as part of a fruitful career, revolutionized recording with the electret microphone in research with Gerhard Sessler at Bell Labs.

James West was born in 1931 in racist rural Virginia; his grandmother was a slave. His curiosity is insatiable and – sometimes destructive. As Ars Technica recounts, he removed his grandfather’s watch but failed to turn it back on, and managed to give himself an electric shock while connecting to a radio. He had to overcome his own parents’ opposition to him pursuing a career in science. Seeing the failures of Black chemists, they refused to pay his college tuition. But West won on his own, attended Temple University, and got an ad for an internship at Bell Labs.

The rest is history: the basis for the electret condenser, the design that would become the most ubiquitous in the world, was laid in that internship, and it started with an accident. The main issue in making a microphone compact is how to deal with power. And the success came from an experiment that West conducted during the internship.

I don’t want to fully contribute to the “lone innovator” model of understanding media history. Even with his large portfolio of patents, it’s the way West works collaboratively that’s most impressive — sometimes involving incredible luck. (This is also the key to why the fight for inclusion ultimately benefits everyone: it effectively makes us all smarter. Or put another way, systemic discrimination makes us all dumber.)

And the story of the breakthrough that led to the development of a working electret mic is truly incredible. Here it is narrated in a research article about its history. (That article is wonderful and worth digesting in full). It all started while Jim was trying to make headphone transducers using Mylar membranes (called Sell transducer), and there was an issue – the sensitivity of the transducer was lost in just a few months:

This “problem” turned into an opportunity, as is often the case with scientific breakthroughs. In 1959 Gerhard Sessler joined Bell Labs and Jim returned from university to investigate the headphone transducer sensitivity problem where he had worked as an intern. In another

those strange coincidences that seem to play an important role in the history of science, Sessler also worked with the Sell transducer. Gerhard used the reciprocal Sell transducer in his Ph.D. work on sound propagation and absorption of gases at high and low pressure and temperature. When Jim began experimenting with the problematic transducer, he inadvertently (but actually) left the DC bias to the Sell receiver disconnected. To his surprise, the receiver began playing back loud with its original sensitivity—it was restored by removing the bias voltage! Kuhl, Schodder, and Schroeder also observed this behavior but did not pursue this phenomenon in their research. At this time Sessler and West were on the way and realized that the problem of sensitivity is due to the fact that the Mylar® polymer becomes slowly charge-compensated. The charge charge causes a slow loss of sensitivity in the Sell transducer. With this understanding of the problem they went to the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics12 which was an encyclopedia of materials at the time, and found that Teflon® had the highest volume resistivity of any material they could find (more at 1018 ohm-cm) . With this discovery, they managed to get some sheets of Teflon®

from Dupont, the creator of Teflon®. They metalized Teflon® with a thin layer of aluminum and created the modern electret microphone by tensioning a charged Teflon® membrane over a metalized backplate.

Elko, Gary W. and KP Harney. “A History of Consumer Microphones: The Electret Condenser Microphone Meets Micro-Electro-Mechanical-Systems.” Acoustics Now 5 (2009): 4. [PDF]

The concept of the electret dates back to 1892, but this is the first time someone has made a working mic.

Here is a good explanation – and as this video producer notes, part of the story here is a Black American collaboration with a German immigrant in the USA. Note both sides – especially as Germany and the USA push anti-immigrant, anti-Black policies.

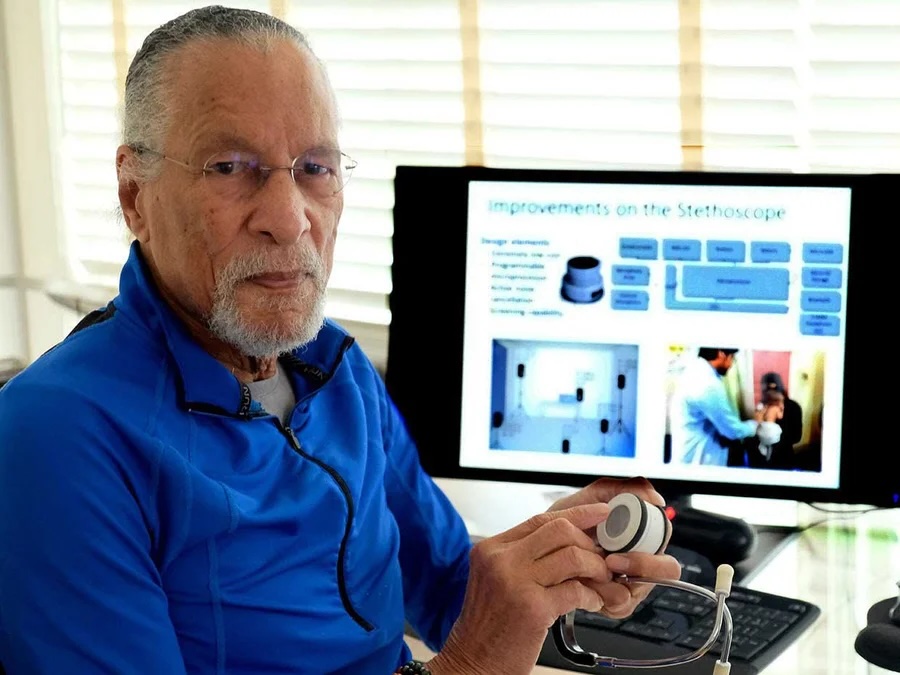

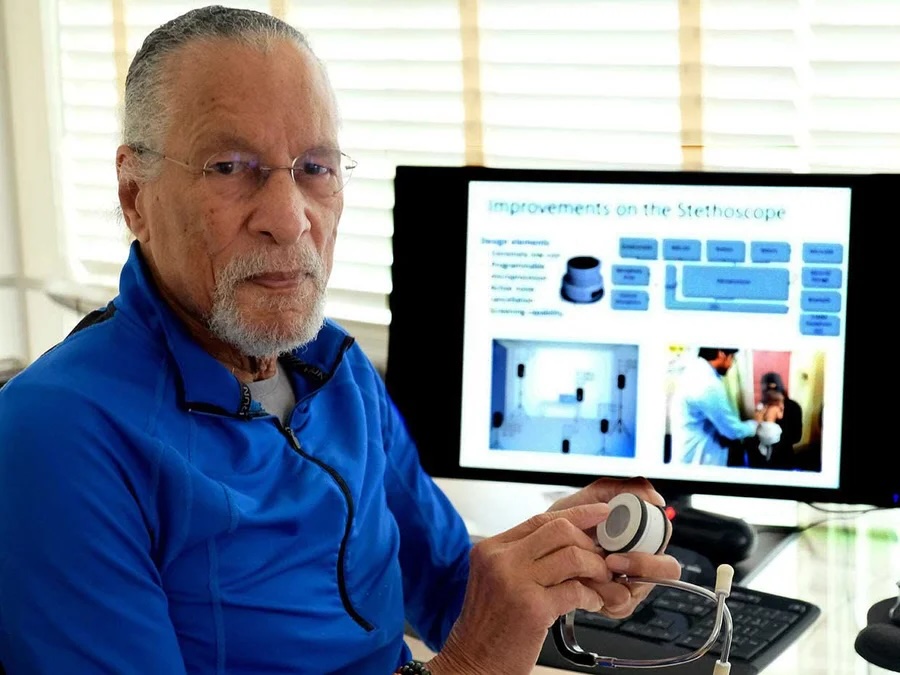

Over 90% of microphones in production each year use this method. West did a lot more – measuring the acoustics of Philharmonic Hall in NYC. He also applies his sound expertise to a variety of research, from tackling noise levels in hospitals to developing a device to detect pneumonia. He has 250 patents to his name.

There are some great interviews with West, too. Electret condensers get the most attention, but his work on sound runs deep – as the connection between audio technology and health care.

(That second video has four parts – see parts II (which hits the electret condenser), III, and IV)

West has happily gained more recognition in recent years, especially in scientific circles, but I’ve noticed that he is often left out of the history of sound. (And in general, we skip a lot of the history of the technologies we use.) That’s a loss, and it’s time to work to correct it.

He ended the fourth interview with an impassioned plea for investment in knowledge, science, and technology, and its ability to preserve the world – plus the lack of inclusion of women and minorities.

“We are in a very dangerous position globally, and no matter how you look at it – from global warming to the complete stupidity of people – threats to the survival of the planet. The solution to these problems is definitely included in knowledge, in what we can learn, what we can do as people to preserve this planet.

It takes a turn, though, as he says what makes him do it is that science is fun. And if that doesn’t describe an overlap in music technology, nothing does.

In addition:

These Three Unseen Black Inventors Shaped Our Lives (also features sugar production and the modern ironing board) [Scientific American]

At 87, this Baltimore inventor has 250 patents to his name — and counting. [The Washington Post]

Listen: James West forever changed the way we hear the world [Ars Technica]

Above photo: Sonavi Labs via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).